by

Joan Trombetti, Writer | March 25, 2008

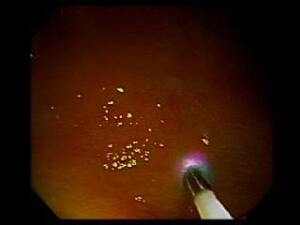

The procedure is performed

before screening a

person by spraying

a short protein attached

to a fluorescent beacon

into the colon.

Doctors at Stanford University School of Medicine are studying a new technique that may be able to detect early stages of colon cancer without a biopsy.

Christopher Contag, Ph.D., associate professor of pediatrics, microbiology and immunology led the study. He said detecting colon cancers is just the first step, and he predicted similar techniques will eventually be able to find a wide range of cancers, monitor cancer treatment and deliver chemotherapies directly to cancerous cells in the colon, stomach, mouth and skin.

Routinely, when doctors find suspicious cells during a colonoscopy, they take a biopsy and send it to a pathology lab to screen for cancer. This can take days, and doctors will only biopsy cancers that are easily visible growths called polyps. Early stage cancers that remain flat are not always found.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 77597

Times Visited: 2716 Ampronix, a Top Master Distributor for Sony Medical, provides Sales, Service & Exchanges for Sony Surgical Displays, Printers, & More. Rely on Us for Expert Support Tailored to Your Needs. Email info@ampronix.com or Call 949-273-8000 for Premier Pricing.

Contag and his group have succeeded in picking up cancer without a biopsy and can identify which cells are cancerous while they are still in the body. The group found a short protein that sticks to colon cells in the early stages of cancer. The procedure is performed before screening a person by spraying that short protein, attached to a fluorescent beacon, into the colon. The protein attaches to any cancerous cells and creates an easily visible fluorescent patch. A miniaturized microscope called Cellvizio Gl developed by Paris-based Mauna Kea Technologies is then used to peer into the colon and look for those spots.

The initial trial was conducted on 15 patients, and the technique detected 82 percent of the polyps that were considered cancerous by a pathologist. Contag believes that this technique, developed in part through the cancer-imaging program at the Stanford Cancer Center, could be adapted to detect cancers in the mouth, esophagus and stomach.

He also feels that real-time screening could be used as a way of seeing whether a chemotherapy regimen is working. The response to the chemotherapy being used could immediately be detected by changes in the cells, and if there is no improvement, doctors could try a new treatment.

This is remarkable given that patients go through several rounds of chemotherapy before the first screen to see if the treatment is working. This is costly not only in terms of dollars, but also prevents patients from finding a more effective treatment that could save their lives. For more information go http://med.stanford.edu/.