by

Loren Bonner, DOTmed News Online Editor | August 10, 2012

From the August 2012 issue of HealthCare Business News magazine

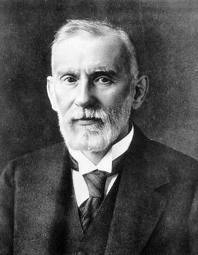

Historically known as the “Great Pox”, Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease caused by a microorganism, was considered an epidemic in Europe throughout most of the 18th and 19th centuries. This all changed in 1910, when Paul Ehrlich, a young German chemist and bacteriologist, developed the first effective treatment against the disease.

Ehrlich discovered Salvarsan, a chemical that treats syphilis microbes. Not only did he come up with the idea that a medical treatment could be custom made to target the specific cause of a disease, but he was also the first to treat disease with chemicals.

Ehrlich was born on March 14, 1854, in Strehlen, Silesia (once a part of Germany, but now a part of Poland). He was exposed to science from an early age. His mother’s cousin, a pathologist, taught him how to stain cells with dye in order to see them better under a microscope. He went on to study science and medicine at the universities of Breslau, Strasbourg, Freiburg, and Leipzig, and continued investigating dye reactions in cells. He graduated with his medical degree in 1878.

Through his early experiments, he discovered that certain cells had an affinity to chemical dyes. He theorized that chemical and physical reactions were taking place and that chemicals could possibly be used to attack harmful microorganisms.

The timing couldn’t have been better. In addition to syphilis, diseases like cholera, typhoid fever and tuberculosis went untreated in Europe during the late 19th century. The medical establishment realized they needed to know more about harmful microorganisms and Ehrlich proved his value while working as a researcher at Charite Hospital in Berlin. In 1882, he heard that the German bacteriologist, Robert Koch, had identified the tuberculosis bacillus but had difficulty recognizing it under microscope. Ehrlich tested several dyes and eventually was able to show Koch an improved method of staining and identifying the tubercle bacillus.

A professional partnership with Koch ensued. In 1891, Ehrlich accepted Koch’s invitation to join him at the Institute for Infectious Diseases, created especially for Koch by the Prussian government. There, Ehrlich worked with Koch and Emil Adolf von Behring to discover a cure for diphtheria.

In 1896, Ehrlich became the director of the Royal Institute for Experimental Therapy, located in Frankfurt. His hope going forward was to find a “magic bullet” against disease—or a chemical compound that would enter the body, attack only the offending microorganisms or malignant cells, and leave healthy tissue untouched. He came up with various chemical agents against a host of dangerous microorganisms. The first, which he named “trypan red,” came in 1904. He found that this dye was capable of killing the parasites in a lab environment that were responsible for sleeping sickness, a deadly disease prevalent in Africa. He finally had proof that his concept of finding killer chemicals could work, and the success of “trypan red” encouraged him to begin testing other chemicals against disease. The dawn of chemotherapy had thus begun.

Next Ehrlich turned his attention to an arsenic compound that had already been used for the treatment of sleeping sickness but had blindness as a side effect. Ehrlich knew that with chemical modifications, the compound could be effective. He oversaw a series of testing at his institute. A breakthrough didn’t occur until the 606th preparation. Ehrlich called his new drug Salvarsan — the chemical cure for syphilis.

Although the drug worked and was widely used, it still needed tweaking. Ehrlich continued testing compounds and eventually found one that didn’t present side effects. The drug was named Neosalvarsan and it became available on the market in 1912 (penicillin would eventually supplant it in the 1940s).

In 1908, he was honored with a Nobel Prize in medicine and physiology, along with Russian bacteriologist Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov, for his work on immunity, particularly his contribution to the diphtheria antitoxin.

In 1914, Ehrlich suffered a mild stroke and a second stroke killed him a year later. This month in medical history, on August 20, 1915, Ehrlich died in Bad Homburg, Prussia (now Germany).