Drug-Resistant Germs? "Nuke" 'Em!

by

Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor | September 11, 2009

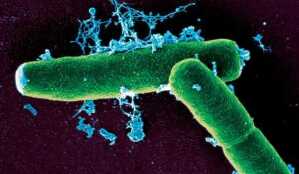

RIT could be useful

against biowarfare agents,

such as B.anthracis, pictured

here in an electron micrograph

A technique normally used to treat cancer might be effective at fighting drug-resistant or otherwise hard-to-kill infections, according to a paper published in the Aug. 24 edition of the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, affiliated with Yeshiva University, in New York, used radioimmunotherapy to treat mice infected with Bacillus anthracis, or anthrax, the deadly bio-warfare agent.

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) has been used to fight cancer for almost 30 years. In RIT, patients are injected with irradiated antibodies. These antibodies then seek out the cells they're hostile to, such as tumor cells, which they kill by delivering their radioactive payload.

Arturo Casadevall, M.D., Ph.D., and his colleague Ekaterina Dadachova, Ph.D., both researchers in microbiology and medicine at Albert Einstein College, reasoned RIT would work perfectly against infections -- in fact, Dr. Dadachova told DOTmed News, she doesn't know why it wasn't tried against them before.

In their study with mice, anthrax-hunting antibodies were labeled with 213-Bismuth, a radionuclide. These antibodies were then introduced into mice infected with anthrax. Predictably, the mice got better. "Significant percentages of mice treated...indefinitely survived otherwise lethal infection with B. anthracis," Dr. Dadachova stated.

Anthrax populations in cultures also declined steeply when the irradiated antibodies were introduced.

One of the most powerful draws of this technique, Dr. Dadachova believes, is that it runs around the drug-resistance trap. In a study published earlier this year, she found that fungal populations didn't become radiation-resistant after a series of RIT treatments. "Drug-resistance mechanisms are based on special molecular 'pumps' in the cells which effectively pump out the cytotoxic drugs," she noted. But interactions between antibodies and the cells they target -- the basis of RIT -- are not governed by these mechanisms. What's more, the radiolabeled antibody delivers so much damage to targeted cells that it excludes "the possibility of [the cells'] survival and giving rise to some radiation-mutant progeny," she added.

RIT is also proven to be extremely safe. "Judging by the experience in cancer patients treated with RIT," Dr. Dadachova remarked, "there are practically no side effects as the treatment is so targeted to the disease sites."

While Dr. Dadachova doesn't recommend using RIT to treat the flu or the common cold, she believes it would be useful for tough cases where normal therapies won't work, such as against drug-resistant bacteria and biological warfare agents, or for immuno-compromised patients, including those with AIDS or who are receiving organ transplants.

Currently, Dr. Dadachova and her colleagues are working on setting up clinical trials using RIT against HIV, which they hope to get going by the end of 2010.